What is it?

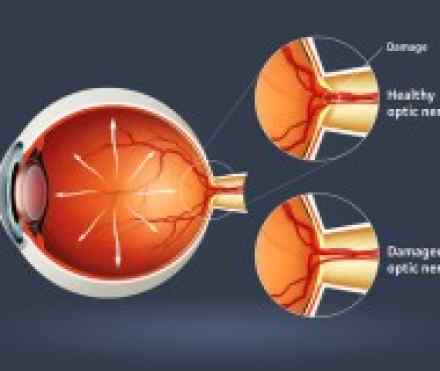

- Glaucoma is not just one disease, but a group of conditions resulting in optic nerve damage, which diminishes sight. Abnormally high pressure inside your eye (intraocular pressure) usually, but not always, causes this damage.

- Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness. Sometimes called the silent thief of sight, glaucoma can damage your vision so gradually you don't notice any loss of vision until the disease is at an advanced stage. The most common type of glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma, has no noticeable signs or symptoms except gradual vision loss.

- Early diagnosis and treatment can minimize or prevent optic nerve damage and limit glaucoma-related vision loss.

Symptoms

The most common types of glaucoma — primary open-angle glaucoma and acute angle-closure glaucoma — have completely different symptoms.

Primary open-angle glaucoma signs and symptoms include:

- Gradual loss of peripheral vision, usually in both eyes

- Tunnel vision in the advanced stages

Acute angle-closure glaucoma signs and symptoms include:

- Severe eye pain

- Nausea and vomiting (accompanying the severe eye pain)

- Sudden onset of visual disturbance, often in low light

- Blurred vision

- Halos around lights

- Reddening of the eye

Both open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma can be primary or secondary conditions. They're called primary when the cause is unknown and secondary when the condition can be traced to a known cause, such as eye injury, inflammation, tumor, or advanced cataract or diabetes. In secondary glaucoma, the signs and symptoms can include those of the primary condition as well as typical glaucoma symptoms.

Causes

For reasons that doctors don't completely understand, increased intraocular pressure is usually associated with the optic nerve damage that characterizes glaucoma. This pressure comes from a buildup of aqueous humor, a fluid naturally and continuously produced in the front of your eye.

Aqueous humor normally exits your eye through a drainage system at the angle where the iris and the cornea meet. When the drainage system doesn't function properly, the aqueous humor can't filter out of the eye at its normal rate, and pressure builds within your eye.

In primary open-angle glaucoma, the drainage angle formed by the cornea and the iris remains open, but the microscopic drainage channels in the angle (called the trabecular meshwork) are partially obstructed, causing the aqueous humor to drain out of the eye too slowly. This leads to fluid backup and a gradual increase of pressure within your eye. Damage to the optic nerve is painless and so slow that a large portion of your vision can be lost before you're even aware of a problem. The exact cause of primary open-angle glaucoma remains unknown.

Angle-closure glaucoma, also called closed-angle glaucoma, occurs when the iris bulges forward to narrow or block the drainage angle formed by the cornea and the iris. As a result, aqueous fluid can no longer access the trabecular meshwork at the angle, so the eye pressure increases abruptly. Angle-closure glaucoma usually occurs suddenly (acute angle-closure glaucoma), but it can also occur gradually (chronic angle-closure glaucoma.)

Many people who develop closed-angle glaucoma have an abnormally narrow drainage angle to begin with. This narrow angle may never cause any problems, so it may go undetected for life.

If you have a narrow drainage angle, sudden dilation of your pupils may trigger acute angle-closure glaucoma. Pupils become dilated in response to darkness, dim light, stress, excitement and certain medications. These medications include antihistamines, such as desloratadine (Clarinex) and cetirizine (Zyrtec); tricyclic antidepressants, such as doxepin (Sinequan) and protriptyline (Vivactil); and eyedrops used to dilate your pupils for a thorough eye exam.

Another form of the disease, poorly understood but not uncommon, is low-tension glaucoma. In this form, optic nerve damage occurs even though eye pressure stays within the normal range. Why this happens is unknown. Some experts believe that people with low-tension glaucoma may have an abnormally sensitive optic nerve or a reduced blood supply to the optic nerve caused by atherosclerosis — an accumulation of fatty deposits (plaques) in the arteries — or another condition limiting circulation. Under these circumstances, even normal pressure on the optic nerve seems to be enough to cause damage.

Pigmentary glaucoma, a type of glaucoma that can develop in young to middle-aged adults, is associated with a dispersion of pigment granules within the eye. The pigment granules appear to arise from the back of the iris. When the granules accumulate on and in the trabecular meshwork, they can interfere with the outflow of aqueous and cause a rise in pressure. Physical activities, such as jogging, sometimes stir up the pigment granules, depositing them on the trabecular meshwork and causing intermittent pressure elevations. This type of glaucoma can usually be easily diagnosed by your ophthalmologist.

Risk factors

Because chronic forms of glaucoma can destroy vision before any signs or symptoms are apparent, be aware of these factors:

- Elevated internal eye pressure (intraocular pressure). If your intraocular pressure is higher than normal, you're at increased risk of developing glaucoma, though not everyone with elevated intraocular pressure develops the disease.

- Age. Everyone older than 60 is at increased risk of glaucoma. For certain population groups such as African-Americans, however, the risk is much higher than expected and the process is detectable at a younger age than is the case for the general population. African-Americans should begin to have their eye pressure monitored before age 30.

- Family history of glaucoma. If you have a family history of glaucoma, you have a much greater risk of developing it. Glaucoma may have a genetic link, meaning there's a defect in one or more genes that may cause certain individuals to be unusually susceptible to the disease. A form of juvenile open-angle glaucoma has been clearly linked to genetic abnormalities.

- Medical conditions. Diabetes increases your risk of developing glaucoma. A history of high blood pressure or heart disease also can increase your risk, as can hypothyroidism.

- Other eye conditions. Severe eye injuries can result in increased eye pressure. Injury can also dislocate the lens, closing the drainage angle. Other risk factors include retinal detachment, eye tumors and eye inflammations, such as chronic uveitis and iritis. Certain types of eye surgery also may trigger secondary glaucoma.

- Nearsightedness. Being nearsighted, which generally means that objects in the distance look fuzzy without glasses or contacts, increases the risk of developing glaucoma.

- Prolonged corticosteroid use. Using corticosteroids for prolonged periods of time appears to put you at risk of getting secondary glaucoma. This is especially true if you use corticosteroids eyedrops.

Complications

If left untreated, glaucoma will cause progressive vision loss, typically in these stages:

- Blind spots in your peripheral vision

- Tunnel vision

- Total blindness

Diagnosis

These are some of the tests that can establish a diagnosis of glaucoma:

- Tonometry. Tonometry is a simple, painless procedure that measures your intraocular pressure, after numbing your eyes with drops. It is usually the initial screening test for glaucoma.

- Test for optic nerve damage. To check the fibers in your optic nerve, your eye doctor uses an instrument that enables him or her to look directly through the pupil to the back of your eye. This can reveal slight changes that may indicate the beginnings of glaucoma.

- Photographs and drawings of the optic nerve. These images may be useful for documenting the severity of the condition.

- Visual field test. To check whether your visual field has been affected by glaucoma, your doctor uses a special test to evaluate your peripheral (side) vision.

- Pachymetry. Your eyes are numbed for this test, which determines the thickness of each cornea, an important factor in diagnosing glaucoma. If you have thick corneas, your eye pressure reading may read artificially high even though you may not have glaucoma. Similarly, people with thin corneas can have normal pressure readings and still have glaucoma.

- Other tests. To distinguish between open-angle glaucoma and angle-closure glaucoma, your eye doctor may use a technique called gonioscopy in which he or she places a special lens on your eye to inspect the drainage angle. Another test, tonography, can measure how quickly fluid drains from your eye.

References:

http://www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/glaucoma.htm

https://nei.nih.gov/health/glaucoma/glaucoma_facts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glaucoma

http://www.ncbi.ie/information-for/eye-health-and-eye-care/eye-conditions/glaucoma

http://www.fightingblindness.ie/glaucoma/

http://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-glaucoma