What is it?

Age-related macular degeneration is a chronic eye disease marked by deterioration of tissue in the part of your eye that's responsible for central vision. The deterioration occurs in the macula, which is in the center of the retina — the layer of tissue on the inside back wall of your eyeball.

Macular degeneration doesn't cause total blindness, but it worsens your quality of life by blurring or causing a blind spot in your central vision. Clear central vision is necessary for reading, driving, recognizing faces and doing detail work.

Macular degeneration tends to affect adults age 50 and older. Dry macular degeneration, in which tissue deterioration is not accompanied by bleeding, is the most common form of the disease.

Symptoms

Dry macular degeneration usually develops gradually and painlessly. You may notice these vision changes:

- The need for increasingly bright light when reading or doing close work

- Increasing difficulty adapting to low light levels, such as when entering a dimly lit restaurant

- Increasing blurriness of printed words

- A decrease in the intensity or brightness of colors

- Difficulty recognizing faces

- Gradual increase in the haziness of your overall vision

- Blurred or blind spot in the center of your visual field combined with a profound drop in the sharpness (acuity) of your central vision

Your vision may falter in one eye while the other eye remains fine for years. You may not notice any or much change because your good eye compensates for the weak one. Your vision and lifestyle begin to be dramatically affected when this condition develops in both eyes.

Hallucinations

Additionally, some people with macular degeneration may experience visual hallucinations as their vision loss becomes more severe. These hallucinations may include unusual patterns, geometric figures, animals or even faces. You might be afraid to discuss these symptoms with your doctors or friends and family for fear you'll be considered crazy. However, such hallucinations aren't a sign of mental illness. In fact, they're so common that there's a name for this phenomenon — Charles Bonnet syndrome.

Causes

The exact cause of dry macular degeneration is unknown, but the condition develops as the eye ages. The initial site of change is not in the light-sensitive cells of the macula, but in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a single layer of cells located just behind the retina close to the back wall of your eye.

Your macula is an area about two-tenths of an inch (5 millimeters) in diameter at the center of your retina. This small part of your eye is responsible for clear vision, particularly in your direct line of sight.

The macula consists of millions of densely packed light-sensitive cells called cones and rods. Cones and rods have two segments: An inner segment controls cell functions and produces proteins responsive to light, and an outer segment stores and makes use of these proteins.

As they absorb light, outer segment proteins become degraded and eventually are shed as waste. Meanwhile, the inner segments continuously provide replacements for the outer segments. One function of the cells of the RPE is to remove the outer segments that are shed.

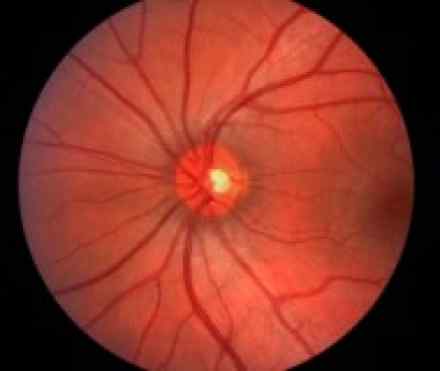

As the eye ages, cells in the RPE begin to deteriorate (atrophy) and lose their pigment. As a consequence, the RPE becomes less efficient in removing outer segment waste. When that happens, the normally uniform reddish color of the macula (as seen with an ophthalmoscope) takes on a mottled appearance. Drusen — yellow, fat-like deposits — begin to appear under the cones and rods. As the drusen and mottled pigmentation continue to develop, your vision gradually deteriorates.

Based on this progression, dry macular degeneration is categorized in three stages:

- Early stage. Several small drusen or a few medium-sized drusen are detected on the macula in one or both eyes. Generally, there's no vision loss in the earliest stage.

- Intermediate stage. Many medium-sized drusen or one or more large drusen are detected in one or both eyes. At this stage, your central vision may start to blur and you may need extra light for reading or doing detail work.

- Advanced stage. Several large drusen, as well as extensive breakdown of light-sensitive cells in the macula, are detected. These features cause a well-defined spot of blurring in your central vision. The blurred area may become larger and more opaque over time.

Macular degeneration almost always starts out as the dry form. Dry macular degeneration may initially affect only one eye but, in most cases, both eyes eventually become involved.

Risk factors

Contributing factors for development of macular degeneration include:

- Age. In the United States, macular degeneration is the leading cause of severe vision loss in people age 60 and older.

- Family history of macular degeneration. If someone in your family had macular degeneration, your odds of developing macular degeneration are higher. In recent years, researchers have identified some of the genes associated with macular degeneration. In the future, genetic screening tests may be helpful for assessing early risk of the disease.

- Race. Macular degeneration is more common in whites than it is in other groups, especially after age 75.

- Sex. Women are more likely than men to develop macular degeneration, and because they tend to live longer, women are more likely to experience the effects of severe vision loss from the disease.

- Cigarette smoking. Exposure to cigarette smoke doubles your risk of macular degeneration. Cigarette smoking is the single most preventable cause of macular degeneration.

- Obesity. Being severely overweight increases the chance that early or intermediate macular degeneration will progress to the more severe form of the disease.

- Light-colored eyes. People with light-colored eyes appear to be at greater risk than do those with darker eyes.

- Exposure to sunlight. Although the retina is more sensitive to shorter wavelengths of light, including ultraviolet (UV) light, only a small percentage of ultraviolet light actually reaches the retina. Most ultraviolet light is filtered by the transparent outer surface of your eye (cornea) and the natural crystalline lens in your eye. Some experts believe that long-term exposure to ultraviolet light may increase your risk of developing macular degeneration, but this risk has not been proved and remains controversial.

- Low levels of nutrients. This includes low blood levels of minerals, such as zinc, and of antioxidant vitamins, such as A, C and E. Antioxidants may protect your cells from oxygen damage (oxidation), which may partially be responsible for the effects of aging and for the development of certain diseases such as macular degeneration.

- Cardiovascular diseases. These include high blood pressure, stroke, heart attack and coronary artery disease with chest pain (angina).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests for macular degeneration may include:

- An eye examination. One of the things your eye doctor looks for while examining the inside of your eye is the presence of drusen and mottled pigmentation in the macula. The eye examination includes a simple test of your central vision and may include testing with an Amsler grid. If you have macular degeneration, when you look at the grid some of the straight lines may seem faded, broken or distorted. By noting where the break or distortion occurs — usually on or near the center of the grid — your eye doctor can better determine the location and extent of your macular damage. Regular screening examinations can detect early signs of macular degeneration before the disease leads to vision loss.

- Angiography. To evaluate the extent of the damage from macular degeneration, your eye doctor may use fluorescein angiography. In this procedure, fluorescein dye is injected into a vein in your arm and photographs are taken of the back of the eye as the dye passes through blood vessels in your retina and choroid. Your doctor then uses these photographs to detect changes in macular pigmentation or to identify small macular blood vessels. Your doctor may also suggest a similar procedure called indocyanine green angiography. Instead of fluorescein, a dye called indocyanine green is used. This test provides information that complements the findings obtained through fluorescein angiography.

- Optical coherence tomography. This noninvasive imaging test helps identify and display areas of retinal thickening or thinning. Such changes are associated with macular degeneration. This test can also reveal the presence of abnormal fluid in and under the retina or the RPE. It's often used to help monitor the response of the retina to macular degeneration treatments.

References

http://www.amd.org/what-is-macular-degeneration/dry-amd/

http://www.medicinenet.com/macular_degeneration/page8.htm

http://www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/amd.htm

http://www.webmd.com/eye-health/macular-degeneration/age-related-macular-degeneration-overview

http://www.hse.ie/eng/health/az/A/AMD/Causes-of-macular-degeneration.html